70th Anniversary of VJ Day

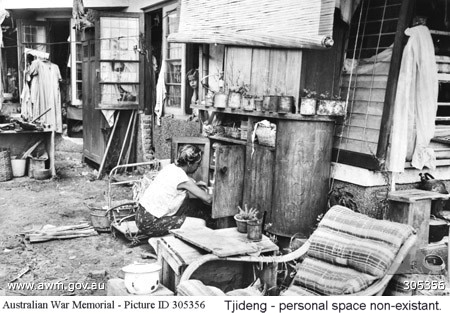

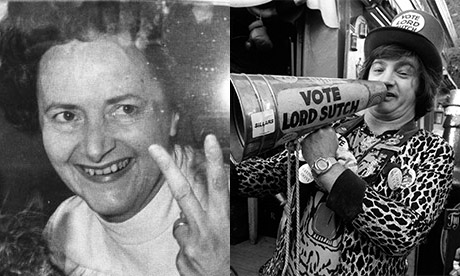

Today’s 70th Anniversary of VJ Day is not simply a historical milestone, but the last commemoration that will be attended in any numbers by those that fought in the Far East. The sight of these veterans, many now in their nineties, will therefore have an added poignancy and solemnity. Their Burma Star berets and Far East Prisoners Of War Association insignia will evoke the horrors of the Pacific Campaign. As they parade down Whitehall the focus will be on the atrocious conditions that they endured as combatants and captives, their pain in the final months made worse for knowing that in Europe the war had ended and people were returning to their normal lives. When the Japanese surrendered, the Commander of the Allied Land Forces in the East, General Slim, told his men: ‘When you go home, don’t worry about what to tell your loved ones and friends about service in Asia. No one will know where you were, or where it is, if you do. You are, and will remain, the Forgotten Army.’ But today the world will remember them, with the focus, inevitably, on the cruelty, starvation, physical neglect and slave labour that came to characterise the War in the East. Marching with these survivors will be another ‘forgotten’ group – the civilian internees. 130,000 Allied civilians, of whom 18,000 were British, also spent three and a half years as ‘Guests of the Emperor’. Already living in the region as missionaries, teachers and planters, men and women were rounded up, separated then trucked away to the 350 internment camps that the Japanese had swiftly created. Some camps were in old government buildings or disused barracks: some were in the jungle: many were simply fenced off areas of cities such as Batavia (now Jakarta) and Bandung. There the women and children were crammed sixty at a time into houses that would normally have accommodated one family. With such appalling overcrowding dysentery and typhus were rife: there were no medicines and education was banned. ‘I used to write my numbers in the dirt, with a stick,’ says Hermance Clegg, mother of the former deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg. Aged 5, she was interned, with her mother and two sisters, in Java’s worst internment camp, Tjideng. ‘My mother engaged a teacher to teach my older sister maths, and for that she had to give her as payment a piece of ‘bread’, which was really just a tiny transparent block of soya, one centimetre thick, which was her daily ration.’

In the camps, women and girls over the age of ten were forced to do ‘useful work’. Those still strong enough to do so had to chop wood in the dapur, the central kitchen, while others had to repair the fencing, or make bamboo coffins for the rapidly increasing number of dead. In addition to these degrading and depressing tasks, the women were brutalised by their guards who regarded their captives with contempt. To look a soldier in the face or fail to bow to him would incur a vicious slapping that could break a nose or loosen teeth. To trade one’s meagre belongings for food with the locals through the fence would be to risk a severe beating, or to have one’s head shaved. Then there was the hated ‘tenko’ or roll call which took place twice a day – more often if the camp Commandant demanded it, which the sadistic Lieutenant Sonei, of Tjideng, frequently did. ‘We had to stand there, then bow from the waist at an angle of 90 degrees,’ Mrs Clegg explains. ‘After that the soldiers counted us but they were very bad at counting and there were thousands of us, and each time they lost their way and had to start all over again. It took ages in the burning sun and we weren’t allowed to wear hats or sit down.'

Even worse than the brutal treatment and exhausting work was the chronic lack of food as the supply of rice to the camps dwindled. By the end of the war the daily ration was half a cup per person per day. ‘What was most poignant of all is that mothers had to resist giving their own rations to their children,’ recalls Hermance Clegg. ‘They knew that they had to keep themselves alive, in order to save their family, but to see your child weakening through lack of food must have been agonising. In this respect I believe that the internees were treated worse than the POWS, because from what I understand, they were given even less food. ’

By the time the camps were liberated, 14,000 civilians had died of starvation, exhaustion or disease. Like the POWs in their loin cloths, the physical and psychological degradation of these women was complete. Like the POWs, they were skeletally thin and half blind with malnutrition. Yet, seventy years on, there’s little general awareness of what they endured. When I published my novel ‘Ghostwritten’ about a Dutch girl interned on Java, the most common reaction from readers was ‘I knew about the POWs, but I’d never heard about this.’

‘I do think that the civilian story in the Far East has been overlooked,’ says military historian, Dr Sarah Ingham. ‘But this is primarily because Europeans had been through so much, with millions displaced and killed, and people trying to come to terms with the enormity of the Holocaust. This is not in any way to belittle what happened to civilian captives in the Far East, but it must have seemed very remote to a Europe where people had suffered so much.’

Perhaps another reason is that the epic scale of the construction projects that the POW’s were forced to labour on - railway lines, bridges and airfields – is more appealing to filmmakers and writers. In the last two years alone there have been two Hollywood films about the Thai Burma Railroad – ‘The Railway Man’ and ‘Unbroken’ - as well as Richard Flanagan’s Booker Prize winning novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. True, there was the successful TV drama, Tenko, about a group of British and Australian women interned in a jungle camp on Sumatra, but that was thirty five years ago, and apart from the 1997 film, ‘Paradise Road’, set in a camp on Sumatra, there’s been almost nothing about the internees since.

But there’s another reason why the male/military narrative has come to dominate the story of the War in the East, which is that the returning soldiers had their regiments to support them, commemorate their courage, and preserve the memory of what they had been through. For the internees there was no such support. They returned to Holland or Britain or Australia and simply got on with their lives. ‘A regiment, or veterans association, where people exchange reminiscences and photos provides an enormous and very important sense of comradeship,’ says Dr Ingham. ‘It must be a huge comfort to be in touch with people who have shared, and understand, the same experience. This is not available to civilians, and so their stories aren’t commemorated in the same way.’

Ghostwritten is published by HarperCollins.

Ghostwritten - RoNA 2015 award nominee

I'm delighted to say that Ghostwritten has been shortlisted for the Romantic Novelists' Association RoNA award (Romantic Novel of the Year) in the Historical Romantic Fiction category. The prize will be announced at a formal ceremony in London on March 16th.

Shadows Over Paradise

I'm very excited about the American edition of 'Ghostwritten' which will be published as 'Shadows Over Paradise' by Random House on Tuesday February 10th. It's the first time I've had a change of title for any of my novels, and although it felt a little strange at first I rather like it. It certainly emphasises the wartime part of the story, on Java.

I also love the cover design. The girl could be from the 1940s, or from the present day. The long grass in which she's lying might be in Cornwall, or on Java. The muted tones suggest nightfall and the distant planes add a note of menace. I'll be doing a Giveaway on Facebook, for US readers, starting on Sunday February 8th. On that day I'll also be doing one of my regular chats about fiction and answering any questions you may have about writing and publishing.

Here's a link to my FaceBook Author Page and I hope to see you there!

Shadows Over Paradise is available from:

How to write good, realistic dialogue

Dialogue is what happens when two or more characters talk to each other. We’ve all read novels in which that conversation is conveyed very awkwardly and this clumsiness pulls us out of the book. Good dialogue, on the other hand, is a pleasure to read, and makes the novel dance along.

Dialogue performs several functions – it moves the story forward, reveals how the characters relate to each other, and creates or builds tension. It also provides a break from the longer descriptive passages which require more concentration to read. I know many people who, before buying a book, will open it to see how much dialogue there is. Too little, and they’re deterred.

To write successful, realistic sounding dialogue you have to develop an ear for how people talk – their vocabulary and accent, the volume at which they speak, their catch-phrases and verbal tics. Having said which, dialogue is not a transcript of how a conversation might read, if recorded. It’s refined, stylised and pared down. Alfred Hitchcock said that a good story was ‘life, with the dull parts taken out’. This observation applies equally to dialogue in which the ‘ums’ and ‘erms’ of normal speech are excised.

Good dialogue tells us who the people that are speaking are – whether they are ‘posh’ or down to earth, caring or ruthless, modest or boastful.Dialogue denotes character more forcefully than description, because it enables the writer to ‘show, not tell.’ For example, a novel’s narrator can inform the reader that such and such a character is a snob; but this is far less effective than if that character were to say, ‘Oh I never travel by bus! Buses are for poor people!’

Another function of dialogue is to tell us about the relationship between the speakers – is one more dominant, interrupting, not listening? Is one trying to please, placate or manipulate the other? The writer needs to consider all these things.

At its simplest, dialogue can move the action along, in just a few lines. Here’s an example.

Megan slept fitfully and dreamed, as she always dreamed, of Tom, then woke with the usual melancholy ache. As she pushed back the sheets she tried to remember his eyes: were they hazel or green? She sighed. After three years she could no longer be sure. She put her feet on the floor, shivered, then reached for her dressing gown at the end of the bed. Before she could put it on she heard rapid, ascending footsteps, then Lynne, shouting.

‘Mummy!’ The door flew open. Lynne stood there, wild-eyed. ‘Mummy!’

Megan’s hand flew to her chest. ‘What is it Lynne? What’s happened?’ She caught her breath, waiting to hear the news that would smash her hopes.

Lynne was crying now. Her hands pressed to her lips. ‘They’ve found him!’ she wept. ‘They’ve found Tom!’

Dialogue can also build tension, as in this example.

Kate stopped suddenly. Her lips were pursed. ‘I need to sit down,’ she said quietly. ‘Can we sit down. Please.’

Daniel looked at her anxiously. ‘Of course.’ They walked towards a nearby bench. ‘Aren’t you well sweetheart? You’re very pale.’

‘I’m… fine,’ Kate answered. But as she sank onto the bench her head dropped to her chest.

Daniel sat beside her. ‘What’s up?’ he murmured but Kate didn’t answer. Daniel was aware of a dog barking, and the distant hum of traffic. A woman pushing a double buggy threw them a curious glance. ‘What is it Kate?’

As Daniel reached for Kate’s hand she lifted her head. ‘Dan…’ She looked at him searchingly. Her lower lip trembled. ‘Dan, there’s something you need to know…’

We understand that Kate and Daniel have been in a relationship, and that this is a moment of change – but we don’t know what the change is yet, and we’re curious to know. The dialogue here also sets the scene in the park, helping the reader to build the images in their head that will make the novel feel authentic and real.

Writing good, realistic dialogue is a challenge, but below are my top tips for doing so successfully.

DO

Be aware of how your characters will sound. A 10 year old boy will not sound the same as an 80 year old woman so make sure that your characters come across in a distinct way. You might give them a particular idiom or catchphrase, but if you do, don’t over-do it. Less is always more.

Punctuate your dialogue correctly. The rules are a new line for each speaker, and the words should be inside the speech marks. In the US a double inverted comma is used for speech marks – “….” but in the UK it’s a single one – ‘…‘. If a character has been interrupted, use a hyphen to indicate that their speech has been broken off. If they trail off, then use ellipsis, with three full stops, like this…

Make it absolutely clear about who is speaking. There’s nothing more annoying for a reader than being unsure and having to go back to work it out. For clarity, restate the name of the speaker now and again, then revert to ‘he said’ or ‘she said’.

Use dialogue not just to convey the words, but to set the scene. Dialogue is not simply about who is saying what to whom, so incorporate touches of description or action to help the reader fully visualise what’s happening.

When you’ve finished writing your dialogue, speak it aloud. This is the best way to know whether or not it’s working successfully.

Be aware of the rhythm and cadence of speech. This means having an almost musical ear for language. The more dialogue you write, the more easily this will come.

Use silence as well as words. We all give ourselves away by what we are not saying, as much as what we are saying.

DON’T

Use dialogue to give information or exposition. For example:

‘Do you remember when we worked at the John Radcliffe hospital?’ Dave said. ‘In Oxford? Back in the 90s?’ He sipped his coffee. ‘And we were both junior house doctors, three years out of medical school, and you were in obstetrics and I was in dermatology, but what you really wanted to specialise in was orthopaedics and I was hoping to go into urology. And do you remember that house we shared with that chiropodist from Birmingham who had six sisters?’ He lowered his cup. ‘Seems so long ago doesn’t it.’

Don’t overdo accents or quirks of speech – it can get tiresome. A little goes a very long way.

Use too many dialogue tags – like ‘whispered’, ‘pondered’, ‘reflected’. ‘Said’ will usually do very well, and the reader absorbs it a bit like punctuation. Too many substitutions like ‘roared’, ‘sang’, ‘screeched’ and ‘threatened’ can distract the reader’s attention.

Let one person speak for too long – it’s dialogue, not a monologue.

A few Suggested Exercises

Write a scene that shows how your main character and a secondary character interact.

Write a scene where your main character/protagonist warns another character that something life-changing or threatening is about to happen to them.

Write a scene where your protagonist is trying to conceal something from a secondary character.

Write a scene that reveals open and growing conflict leading to a blazing row between the protagonist and another character.

Write a scene where a secondary character confesses something dreadful to your protagonist.

—

Isabel Wolff’s latest novel, Shadows Over Paradise (published in the UK as Ghostwritten) is published by Random House Inc. in paperback and on Amazon Kindle on February 10th

Shadows Over Paradise is available from:

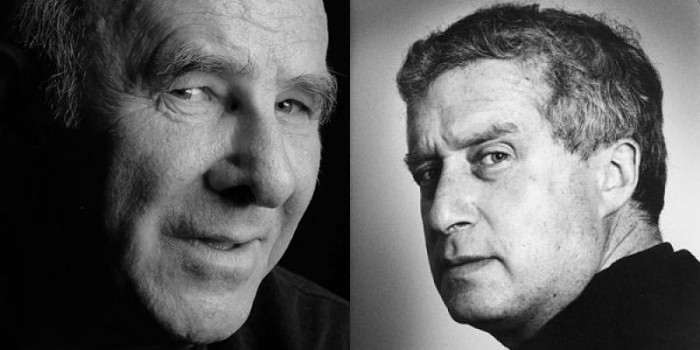

As Featured on ‘Interstellar’...

Most writers struggle to get attention for their novels; grateful for a review or two in the national press or in the women's magazines, we do our best to get coverage that will draw attention to our books. We write feature articles and reach out to literary bloggers: we post about our books on Facebook and Tweet. Anything to try and make our work visible and discoverable in the sea of published books. But this week I got help from a completely unexpected quarter, when Christopher Nolan's new blockbuster, 'Interstellar', came out. I went to see it with a girlfriend who, as the film began, suddenly grabbed my arm and let out a gasp. And I gasped too because the camera was tracking along a book shelf, on which, clearly visible, was my third novel, 'Out of the Blue'. It was there for a second or two at most, but we had both seen it and I knew that millions of other cinema-goers would see it too. I was of course thrilled beyond words - what a fabulous plug! - but I was also mystified as to why it was there. Among the other novels on the shelf I had recognised 'Time's Arrow' by Martin Amis, and 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' by Marquez. By the end of the film I could see why those titles might have resonated with Christopher Nolan. 'Interstellar' is about space and time travel, and about astronauts, cryo-frozen, sleeping their way through their intergalactic voyage. But why 'Out of the Blue'? It has the feeling of the sky of course, but that's the only reason that I can think of to make it fit with Nolan's themes. Since then I've seen online forums that debate the meaning of the featured books. Someone pointed out that 'Out of the Blue' was published on February 1st 2003, which was the day of the Columbia space shuttle disaster. I took my courage in my hands and tweeted to @Interstellar, saying that I was of course delighted to see my book at the start of the film, but would love to find out if there was any particular reason for it being there. If I get a reply, I shall let you all know.

More on The Forgotten Women of the War in the East

First published on Books By Women

Isabel Wolff’s latest novel, Ghostwritten, is a poignant story about a Dutch girl and her family struggling to survive in a Japanese internment camp on Java. Isabel tells WWWB what drew her to this neglected part of World War 2 history.

I’ve always had a fascination for the Pacific War. It began at 8, when I learned that my parents’ friend, Dennis, had been a POW in Burma. My mother told me, in hushed tones, that Denis had ‘suffered terribly’ and seen ‘terrible things’ although she didn’t want to say what those things might have been.

When I was 12, I read A Town Like Alice, set in occupied Malaya, a novel that has stayed with me all my life. And a few years later I watched, avidly, the TV drama series, Tenko, about a group of British and Australian women struggling to survive in a Japanese prison camp. These things came together in my mind and I decided to write a novel about the internment of women and children in the Far East.

There were many locations in which Ghostwritten could have been set: civilian men, women and children were interned right across the region in Singapore, Borneo, Malaya, the Philippines, China and Hong Kong. I chose to set it in the Dutch East Indies, on Java, where the Japanese camps were the most numerous. They were also, by and large, the worst.

As I planned the story I read history books about the period and scholarly articles; I visited survivors’ websites and read their accounts. I interviewed two elderly women who as children had been interned on Java and still vividly remembered the daily privation, brutality and fear.

I went to Java and saw the places in Jakarta (formerly Batavia) and Bandung where thousands of women had been interned. And as I stood in the Dutch War Cemetery and gazed at the white crosses for women and children that stretched away from me in all directions I was saddened to think how little their suffering is known. For the truth is that the male/military/POW narrative has come to define the story of the War in the East.

I wondered why this should be. Perhaps it’s because the Thai Burma ‘Death Railway’ was so ‘epic’ and monstrous, and has been dramatized with vivid horror in films such as Bridge on the River Kwai. More likely it’s because the soldiers had their army, their regiments and their comrades to extol their courage, and to make sure that their story was known.

Yet the same number of civilians – 130,000, mostly women and children – were also imprisoned by the Japanese. These were Dutch planters, missionaries, civil servants and teachers who after the fall of Java were herded into hundreds of concentration camps. Like the POWs, the civilian prisoners suffered starvation, forced labour, cruelty and death. Yet they have had no-one to speak up for them.

This became apparent to me this spring, when Ghostwritten was published. One of the most common responses from readers was: ‘I had never heard about this.’ Perhaps this wasn’t so surprising, I reflected, given that you now have to be over 45 to remember Tenko. There was the film, Paradise Road, about a group of American and Dutch women in a camp on Sumatra, but that was back in 1997.

Since then no films or novels have focussed on the civilian story, ‘though writers and directors continue to be fascinated by the suffering of the military men. This year alone there have been two Hollywood films – The Railway Man and the soon-to-be-released Unbroken about the Olympic runner and Japanese camp survivor, Louis Zamperini.

There has also been Richard Flanagan’s magnificent, Man Booker prize-winning novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. I felt proud to be writing about what these women and children had been through. Yet as more reader comments came in, the ones that surprised me the most were: ‘I had never heard about this – and I’m Dutch!’

Dutch friends tell me that in Holland this part of wartime history is not widely taught, compared to the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, and the Holocaust. In their memoirs the internees who were repatriated to Holland in 1946 tell of further alienation in which, far from being welcomed back to the mother country, they were bitterly resented. Because they were emaciated – most had lost 30% of their body weight – they were given extra food coupons.

In grocery shops they would get sharp looks and sharp remarks. ‘Why should we look after you?’ was a frequent cry. ‘While you were sunning yourselves in the tropics, we had the Nazis!’ After all, the Dutch had themselves been starved during the terrible ‘Hunger Winter’ when the Germans blockaded northern Holland for six months. Little wonder then that there was no compassion for these ‘pampered colonials’ who were widely referred to as ‘Uitzuigers’ or ‘leeches’.

It was as though there had been two, quite different wars, and the repatriates soon learned not to talk about theirs. Their war was the war of starvation, dysentery, savage beatings and bamboo fencing. In time, survivors began to tell their story in memoirs, all with titles redolent of a lost Eden: Dark Skies Over Paradise; Java Lost and Stolen Childhood. And now there’s a novel, Ghostwritten, which has their ordeal, and their courage, at its heart.

The Forgotten Women of the ‘War in the East’

BBC Worldwide

19th October 2014

Amid all this, the greatest fear for mothers of boys was that their sons would be taken away. The age at which boys were transferred to men's camps dropped from 15 at the start of the war, to 13 then 11, until by 1944 boys of 10 were being transported. As they waited to climb on to the lorries they would cling to their mothers, not knowing whether they'd ever see them again.

By the time liberation came on 15 August 1945, the degradation of these women was complete. Like the POWs in their loin cloths, they had virtually no clothes, many wearing old tea towels for bras, and "sandals" fashioned out of strips of rubber tyres.

Like the POWs they were skeletally thin, half-blind with malnutrition and, as with the POWs, huge numbers had died.

I have no wish to diminish the heroic Prisoners of War that Flanagan has written about with such brilliance, or ever to forget what they endured. But thousands of women and children also lived with hunger, disease, cruelty and death, and we should remember their ordeal, and their courage, too.

With such chronic overcrowding, poor sanitation was the norm, and dysentery and typhus flourished, along with scabies, bedbugs and lice. Education was banned - children would write their numbers with a stick in the dirt - and females aged between 11 and 60 all had to do "useful work". Many women were "furniture ladies", whose job was to empty houses of furniture, then take it to another, already emptied house, for the future use of the Japanese.

Working in pairs, they would lift tables, cupboards and even pianos on to a "buffalo" cart. But instead of the cart being pulled by a buffalo the women would have to put on the harness and haul it themselves. Others worked in the dapur or central kitchen where they would chop firewood and scrub the old oil barrels that were used as giant saucepans. Some repaired the hated gedek - the fence - while others had to scoop sewage out of the overflowing latrines or make coffins for the ever increasing number of dead.

In addition to this distressing, undignified and exhausting work, the women were subjected to constant brutality. To look a soldier in the eye, or fail to bow to him instantly would incur a vicious slapping that could break a nose, or loosen teeth. At Tenko, or roll call, which took place twice a day, the internees had to stand for hours in the blazing sun, with no hats allowed and not even the elderly or children allowed to sit down.

Once Japan had conquered South-East Asia, the Europeans, Americans and Australians who had been living there as planters, teachers, missionaries and civil servants were rounded up and trucked away to the 300 "civilian assembly areas" - in reality concentration camps - that the Japanese had created. Ten thousand British were interned in China, Singapore and Hong Kong, while 3,000 Americans were interned in the Philippines, at Santo Tomas.

By far the largest group were the 108,000 Dutch civilians, 62,000 of them women and children, who were sent to camps on Java, Sumatra, Borneo and Timor. Their ordeal was to last three and half years and would claim the lives of 13,000, due to starvation, exhaustion and disease. Yet when I published my novel, Ghostwritten, about the internment on Java of a Dutch girl and her family, the most frequent response from readers to this part of wartime history was: "I had never heard about this."

You have to be over 45 to remember the 1980s TV drama, Tenko, about a group of British and Australian women interned in a camp on Sumatra, which is also the setting for the 1997 film, Paradise Road, about American and Dutch women struggling to survive in a camp in Palembang.

Richard Flanagan's The Narrow Road to the Deep North has won this year's Man Booker Prize. But there's more to the "war in the East" than the horrors of the Burma railway says novelist Isabel Wolff.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North is a magnificent novel and a worthy winner of the Man Booker Prize. Its story of Tasmanian army surgeon Dorrigo Evans and his fight to save the men under his command from starvation, disease, and the relentless brutality of their Japanese captors, will stay with me for the rest of my life.

The book is a powerful addition to the canon of films and literature that dramatise the horrors of life as a POW in the Pacific War. Bridge On the River Kwai, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, The Railway Man and the soon-to-be-released Unbroken, about the Olympic runner and Japanese camp survivor, Louis Zamperini, all focus on the suffering of Allied soldiers in the Far East.

Indeed, when we reflect on that part of World War Two we think, automatically, of these brave military men, of whom there were 132,000. Yet there were 130,000 Allied civilians in the region - predominantly women and children - who also endured appalling privation and cruelty, but whose story is barely known.

But where the Thai-Burma Railway continues to fascinate writers and historians, with two Hollywood films and a major novel this year alone, there's little awareness of what the civilians endured.

For most, a near paradisal life in the tropics had come to an abrupt end with the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, followed soon after by the Fall of Singapore. While the Allied troops were sent to slave on construction projects in Burma, Singapore and Japan, the civilians were imprisoned in what were, for the most part, segregated camps.

The men's camps, for men and boys over the age of 15, were in former government buildings and disused barracks, while the women and children's camps were fenced-off areas of cities such as Batavia (now Jakarta) and Bandung. In camps like these women and children were crammed, 50 or 60 at a time, into houses that would normally have accommodated one family.

UK Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg's mother, Hermance, was in Camp Tjideng in Batavia, with her mother and sisters. She remembers having to bow deeply towards Japan at Tenko, "with our little fingers on the side seams of our skirt. If we did not do it properly we were beaten." Another punishment, head shaving, was so common that the women would simply wrap a scarf round their bloodied scalp and carry on.

Worse even than these sanctions was the fear of starvation as the rations of what passed for food - tapioca gruel - dwindled to half a cup per person a day. Desperate to keep their children alive, women would catch frogs, lizards and snails and boil them in a tin cup on the back of their irons.

The more daring risked being savagely beaten or even executed, as they crept to the gedek to trade their meagre possessions with local people for a banana or a couple of eggs. The internees became so obsessed with food that they would feverishly swap recipes, writing out the ingredients, discussing the method then mentally savouring the delicious dish that they would never get to eat.

Amid all this, the greatest fear for mothers of boys was that their sons would be taken away. The age at which boys were transferred to men's camps dropped from 15 at the start of the war, to 13 then 11, until by 1944 boys of 10 were being transported. As they waited to climb on to the lorries they would cling to their mothers, not knowing whether they'd ever see them again.

By the time liberation came on 15 August 1945, the degradation of these women was complete. Like the POWs in their loin cloths, they had virtually no clothes, many wearing old tea towels for bras, and "sandals" fashioned out of strips of rubber tyres.

Like the POWs they were skeletally thin, half-blind with malnutrition and, as with the POWs, huge numbers had died.

I have no wish to diminish the heroic Prisoners of War that Flanagan has written about with such brilliance, or ever to forget what they endured. But thousands of women and children also lived with hunger, disease, cruelty and death, and we should remember their ordeal, and their courage, too.

Isabel Wolff's novel, Ghostwritten, was published in March 2014

The Other Side of the POW Story

I was thrilled when Richard Flanagan’s ‘The Narrow Road to the Deep North’ won this year’s Man Booker Prize. Set on the Thai-Burma ‘Death Railway’ it’s a magnificent novel and a powerful addition to the films and books – ‘Bridge On the River Kwai’, ‘The Railway Man’ etc., that focus on the fate of the Allied POWs in the Far East. There were 130,000 of these men, who suffered starvation, disease, and relentless brutality. But there were 132,000 Allied civilians in the region, most of them women and children, who also endured dreadful privation and cruelty, yet whose story is barely known. These were the families of European and Australian planters, teachers, missionaries and civil servants. They are also the heroines of my new novel, ‘Ghostwritten’, about a Dutch girl, Klara, and her family, and their struggle to survive in a prison camp on Java.

30 years ago the TV series ‘Tenko’ dramatized the imprisonment of women and children in a Japanese internment camp on Sumatra, as did the 1997 film, ‘Paradise Road’. But ‘Ghostwritten’ is the only novel I know of, since then, that focuses on the reality of daily life in these appalling camps. Overcrowding was so chronic that dysentery and cholera flourished, along with bedbugs and lice. There was little or no sanitation and education was banned – children would write their numbers and letters in the dirt. The prisoners had to stand for hours in the blazing sun at roll call, or Tenko, and all females between 10 and 60 had to work. Many had to lift heavy furniture, others had to chop firewood for the central kitchen, scoop sewage out of the overflowing latrines or make coffins for the ever increasing number of dead. And amidst all this they were being slowly starved, as the rations dwindled to one cup of rice per person per day. The women also faced routine violence from their guards. If a woman looked a soldier in the face or failed to bow to him instantly they were given a vicious slapping that could break their nose or loosen teeth. If they traded their possessions for food at the hated gedek fence, they could be beaten to the ground, or have their heads shaved. In camps were the Commandant was particularly sadistic, some women were executed while others were ‘punished’ by being tied to a chair in the sun.

‘Ghostwritten’ is a story of survival – it’s about women being tested to destruction during a terrible war. It’s received wonderful reviews I’m happy to say, but one of the most frequent comments from readers is that they ‘had no idea’ about this part of history. I believe that this is because the story of the ‘War in the East’ has come to be dominated by the male/military narrative: yet the experience of internment, for a woman, was just as harrowing as captivity was for any man. By the time the Far East was liberated the degradation of these women was complete. Like the POWs in their loin cloths, they had virtually no clothes, many wearing old tea towels for bras, and ‘sandals’ made out of rubber tyres. Like the POWS, they were emaciated and half blind with malnutrition and, like the POWS, many thousands had died. I have no wish to diminish the heroic Prisoners of War or ever to forget what they endured; but thousands of women and children also lived with hunger, disease, cruelty and death, and we should remember their ordeal, and their courage too.

Isabel Wolff October 16th 2014

Ghostwritten’ is published by HarperCollins in paperback and on Amazon Kindle.

The novel will be published in the U.S. on February 10th with the title, ’Shadows Over Paradise’

Guest Adjudicator in the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award

I'm thrilled and honoured to have been asked to be the guest adjudicator in the Authors' Club Best First Novel Award. The six shortlisted novels have now been chosen and I'll be reading them over the next month, and announcing the winner at the Awards Ceremony on Tuesday June 3rd. For details of the shortlisted novels please click on the link below.

My Writing Room

Novelicious.com - Thursday 3rd April 2014

We live in a tall thin house in Notting Hill and my writing room is down in the basement, dark and deep, with bars on the windows - my own personal dungeon.

I have taken the photo very close in out of shame at the general untidiness. The desk is nothing like as well organised as it appears here, the hinterland behind the computer strewn with books, used coffee mugs, bars of chocolate and general bric-a-brac. I have tidied it for the photo, but within an hour it will resemble a mini-landfill once more.

The shelves above it are piled high with reference books that I never, ever open, and piles of the various foreign editions of my novels. The overseas publishers kindly send me 10 – sometimes 20 – of each, and there are only so many that my local Oxfam is prepared to take. I don’t like to throw them away in case I one day get to know someone Indonesian, Latvian or Thai, on whom I can press a copy, whether they want one or not. So these translations sit there, stacked up like bricks.

My computer screen is studded with sticky labels reminding me of the pin codes and passwords for my bank and building society accounts: burglars will thank me for this one day.

The keyboard is grimy and when turned upside down releases enough crumbs to make half a packet of Rich Tea. I have my iPad mini to hand, so that I can distract myself from the writing process by seeing my e-mails and Twitter interactions come in.

The things of sentimental value that I have are the nursery school paintings done by my children, a photo of my parents, and one of myself with my partner Greg. There’s also a photograph of my grandmother, when she was young and living in India, wearing a beautiful Pierrot costume. I think this may lead to a novel one day. I love the small clock in the shape of a book, which Wendy Holden gave me. On my screen saver is our cocker spaniel, Alfie. He’s eight months old and we adore him. I cannot write a word unless he is lying at my feet.

Exclusive interview with Isabel Wolff

by Lucy Walton, Female First, 26th March 2014

‘Ghostwritten’ is set in present day Cornwall and on Java during World War 2. As with Tenko and The Railway Man it’s a story of the struggle to survive - and to retain one’s humanity - in the most difficult conditions a human can face. The novel is centred on Klara Tregear, who lives on a coastal farm in Cornwall. But Klara grew up in the tropics, on a plantation in Java, and was interned in a prison camp with her mother and little brother during the Japanese occupation. Klara has never spoken about what she went through in that terrible place. Now, approaching 80, she has decided to tell her story, and commissions a young ghost writer, Jenni, to help her do so.

Please tell us about the character of Jenni

Jenni is a complex character. Shunning the limelight, she has chosen to be a ghost writer, happy to work for months at a time on books that will not even bear her name. The reason for Jenni’s self- effacement is that she fears exposure. Were she to become well known, then people might discover the secret that she has kept for so long – a secret that even those closest to her do not know. For, when she was nine, Jenni made a mistake that led to a tragedy, and she’s still haunted by this, twenty five years on. So she prefers to stay in the shadows, and her work - immersing herself in the memories of others - means that she doesn’t have to think about her own painful memories too much. But through her growing friendship with Klara, Jenni may now have the chance to lay to rest the ghosts from her past.

How much has your background in English helped you to write this book?

Reading English at university has helped me to write not just this book, but all my ten novels, in that in order to become a writer, you first have to be a reader. Studying English meant that I was not only reading a huge deal of literature, but had to analyse the texts and decide why it was that they worked. I had to understand the story structure, the characterisation, the symbolism and the tone. I still think about these things when writing my own novels.

To what extent has your journalistic background affected your novel writing skills?

My journalistic background has been paramount in becoming a novelist, and I don’t think that I’d have become one without it. I was a radio reporter at the BBC World Service for 12 years, and the skills that I acquired there have stood me in very good stead. I learned how to write scripted links that would advance the story, but also had a bit of sparkle, to keep the audience engaged. I was also writing articles for newspapers and magazines, and from print journalism I learned how to prioritise the elements of the story, to make the piece flow. It’s not so different doing that with a novel, except that it’s on a much larger scale: I’m writing one hundred thousand words, rather than one thousand, but the technique is basically the same.

Please tell us about your research process in the book

My novels have changed over the years, with the earlier romantic comedies such as ‘The Making of Minty Malone’ and ‘Rescuing Rose’ giving way to novels like ‘A Vintage Affair’ and ‘The Very Picture of You’, which are set in the present and the past. ‘Ghostwritten’ continues this change, and it required a huge amount of research, because the war-time part is so important. The story that Klara tells Jenni is based on dozens of true stories about the Dutch, English and Australian women and children who were interned in prison camps throughout the Dutch East Indies during the war. I had to immerse myself in their remembered world, and so I interviewed two women, one in London, and one in the U.S., who had been imprisoned on Java as children and whose memories of this time were still vivid, seventy years on. I read the memoirs of several Dutch women who had been interned, and I visited survivors’ websites. I went to Java myself. Once I felt that I really knew this world of a tropical paradise that had become a living hell, I placed in it my fictional story of Klara and her brother Peter, her best friend Flora, the treacherous neighbour, Mrs Dekker, and the camp commandant, Konichi Sonei.

What made you want to write about the Japanese camps in Java?

When writing a novel I always start with what the heroine does for a living, because then from this everything else will flow. Once I knew that my heroine, Jenni, was going to be a ghost writer I had to decide what the ghost written story that she writes was going to be. I knew that I wanted it to be a wartime memoir, but worried that the war in Europe has been written about so much. At the same time I had always been very interested in the Pacific war, and so I turned my thoughts towards that. And it seemed to me that when we think of the war in the Pacific, we think of the poor POW’s who were forced to slave on the railways in Burma and Sumatra. But there were a hundred thousand civilian prisoners of war too, most of them women and children. I read of their struggle with starvation, disease and the cruelty of their Japanese captors. I tried to imagine what it would be like to be beaten, or have my head shaved, or to stand in the burning sun at tenko, for hours on end, with a child in my arms. What these thousands of women endured is not widely known. I decided that my novel would put their ordeal, and their courage, at its heart.

What is next for you?

I’m going to write a novel set in India – more than that I don’t really know at this very early stage!

Isabel Wolff’s Favourite Far-Eastern Novels

'We Love This Book', 26th March 2014

Isabel Wolff’s new novel, Ghostwritten, is set on Java during the Japanese invasion. She chooses her five favourite novels set in the Far East.

A TOWN LIKE ALICE

Nevil Shute

I read this wonderful novel when I was 12, and its quiet heroine, Jean Paget, and the man who is crucified for her, Joe Harman, have stayed with me all my life. Shute’s descriptions are so vivid that you can almost feel the stones beneath the women and children’s feet and the sun burning their skin as they’re marched across Malaya by their Japanese guards. Despite being a harrowing read, the book’s message is one of hope - that love can survive the most desperate odds.

I read this wonderful novel when I was 12, and its quiet heroine, Jean Paget, and the man who is crucified for her, Joe Harman, have stayed with me all my life. Shute’s descriptions are so vivid that you can almost feel the stones beneath the women and children’s feet and the sun burning their skin as they’re marched across Malaya by their Japanese guards. Despite being a harrowing read, the book’s message is one of hope - that love can survive the most desperate odds.

EMPIRE OF THE SUN

EMPIRE OF THE SUN

J.G. Ballard

This brilliantly written coming of age story, set in the early 1940s, is about war seen through the eyes of a child. 11-year-old Jim lives with his ex-pat parents in China, but is separated from them after the Japanese invasion and is interned in the Lunghua prison camp near Shangai. Through the horror and the destruction, and the constant threat of starvation, Jim must live by his wits to survive. One of the great novels of the 20th Century.

THE PAINTED VEIL

THE PAINTED VEIL

Somerset Maugham

Set on Hong Kong in the 1920s, The Painted Veil is a story of a woman’s moral and spiritual journey. Selfish socialite Kitty is married to worthy scientist, Walter, but is having an affair with a charming colonial secretary, Charles. When Walter finds out he extracts an unusual revenge. He lets Kitty choose either divorce - which would be her social death – or for her to accompany him to a cholera-infested part of China. Maugham allows Kitty to live, but caring for the sick changes her forever.

THE SAMURAI'S DAUGHTER

THE SAMURAI'S DAUGHTER

Lesley Downer

Set in 1800s Japan against the backdrop of the Satsuma Rebellion, this is the beautifully written story of Taka, a Samurai’s daughter, who falls in love with a servant, Nobu. But Nobu is not just low-born, he’s from an enemy clan. With Japan heading for a bitter civil war Taka is forced to choose between her family and the man she loves. The depictions of life in Japan during this time are fascinating and the storyline is riveting.

AN INSULAR POSSESSION

AN INSULAR POSSESSION

Timothy Mo

A wonderful historical novel about the beginnings of Hong Kong. Set in Canton in the early 1880s, its American protagonists, Walter Eastman and Gideon Chase, set up a newspaper as a caustic and parodic mouthpiece for their anti-opium trade views. As the paper prospers, Anglo-Chinese relations fail and the first Opium War begins. With a sprawling cast of traders, tricksters, artists and warriors this is an exciting and rewarding read.

Guide to Writing & Getting Published

People often ask me how to how to get published. So here, for any aspiring writers out there is the advice I usually give.

First of all, ask yourself if you really are the sort of person who's going to write. For example, do you have a running commentary going through your head, like a film script, describing what's going on around you? Do you find you're earwigging madly on buses and trains? Do you read a lot, and do you actively analyse what you read? Do you go to lots of films and plays? Have you looked into doing creative writing courses at your local college? Have you ever wanted to work with books, in a bookshop or publishing house?

If you can answer 'yes' to any of the above, then you may well be the sort of person who could write. But when writers laughingly trot out the cliche about it being 99% perspiration and only 1% inspiration, believe me, they are not lying - writing books is a sweat. But it's a hugely enjoyable sweat if you're confident that you have a good story to tell. So if you feel that you do, then crack on and make a start.

Getting Started

How do you get started? Well, you have to have a plan. Some writers just begin their novels without really knowing where they're going - and if it works for them, then fine. But I find I need to have a proper structure. So I decide what the main story line is going to be and this takes no more than three or four sides of typed A4. From that blueprint I then flesh out the synopsis. You may find you're not able to write the full synopsis - after all some of the main ideas will come to you as you write - but I always try and have at least 60 per cent of the story-line there. Once you've done that, divide the synopsis into chapters, each chapter being summarised in no more than half a page of A4 - in other words, you should have about two chapters per page.

Characters

I think it's best to have no more than six main characters, as it's difficult for your reader to care about the characters, or follow their progress, if there are too many of them galloping across the page. So decide who the main 'dramatis personae' are, how they are going to interconnect (without relying on coincidence of course - a total yawn), and then make detailed notes about them. Who are they? Where do they live? What sort of problems do they have? What do they do? Who are their friends? What are/were their parents like? What do they wear, smoke, eat and drive? Most importantly, what motivates them?

I often think that being a novelist is like being a shrink - you have to build up a detailed psychological profile of all your main characters - and then stick to it so that they are consistent and credible. And if they do act 'out of character' then you have to give them a clear motivation for doing so. Successful novels contain characters who feel real to the reader and whose behaviour they can understand (even if they don't approve), and sometimes second-guess. By the time the reader turns the last page, they should feel as though they know your characters personally, and have understood them very well, (even if they haven't always liked them that much).

Above all, make your characters rounded, not flat. We are all a mixture of good and bad, so it's a bore if a character is completely 'virtuous' while another is purely 'vicious'. Life is not about 'goodies and baddies', 'nasties and nicies.' Some books - bad ones - read like second rate Westerns - it's all injuns and cowboys. So set out to make your characters a credible mix. If you have a heroine/hero who is flawed, then that flaw should not be too 'unforgivable' (i.e. killing people) otherwise your reader won't like them enough to follow their progress to the end. Equally, if you have a nasty character, then try and make the reader understand what motivates them to be nasty. And try and give them one redeeming quality, or perhaps make them pitiable, rather than wholly unpleasant, as that makes for a more textured, realistic personality.

You may to choose to have your main character an anti-heroine or anti-hero which is fine, so long as they are either very clever/funny/brave or just downright entertaining so that we put up with them behaving in an appalling way. Michael Dibdin's 'Dirty Tricks' (see Highly Recommended) is a good example of this, as is Alexander Portnoy in Philip Roth's hilarious 'Portnoy's Complaint', and also the scheming Becky Sharp in 'Vanity Fair'.

Plot

Very often the plot will develop from the characters. Things will happen to the hero/heroine, because of the way they are. So don't just put in a plot development because you want to have a 'wedding scene', or a 'funeral scene' or a 'fight scene' - the action should follow as a direct result of the characters' behaviour, because that is true to life. Things happen to us, or we do certain things, because of who we are. So don't just construct a 'dramatic' plot, and then fit the characters into it because that will probably feel synthetic and fake. The action should flow, to a great extent, from the characterisation.

Equally don't insert scenes just for the fun of it. Set pieces - for example a charity ball, or a football match or an excruciating dinner party - can be fun to write (and read) but they shouldn't be side-shows. They should be there because they are relevant to the story-line. So don't just have your heroine going to Rome for the weekend, for example, unless there's a reason why she should be going there, and because something will happen to her there which connects with the rest of the plot, and moves it on. Everything should add up and make sense, so no sight-seeing. It's self-indulgent and it's frustrating to read, because the reader will rightly think to themselves, 'so what?'

The World of the Book

When you write a novel, you are conjuring a whole world, so it certainly helps to know a lot about that world. It's no good having your main character being a doctor or a vet if you know nothing about it. So the old axiom, 'write about what you know' is true - though not exclusively. Certainly, use your life experience - we all do - as it will feel authentic. Ransack your memory for everything you've ever done and everyone you've ever met - however much you might have hated it/them at the time. If you do stray into 'foreign' territory, then make sure you do thorough research. If your main character's a weather forecaster, for example, as is Faith in 'Out of the Blue', then you have to do extensive reading, interviews and detailed research so that you can convey what a weather forecaster does in a credible way. You don't have to go into grinding detail - which would only hold up the plot (or look as though you're showing off that you've done your research). But do go into enough detail so that the reader knows that it's realistically portrayed.

Writers are always alert to stories. I find that some of my plot lines have come from real life events I've read about in magazines, or newspapers, or stories I've heard on the radio, or seen on TV. These stories are around us all the time and you should be listening, and thinking about how these narrative threads might go into the tapestry of your synopsis. For example, listening to stories about adoption on Radio Four's Home Truths partly inspired one of the main themes in 'Rescuing Rose'. So be alert to stories - they are everywhere you look. Equally keep a notebook in your bag, and by your bed, to jot down any good thoughts you have during the day.

Another important piece of advice is to read around the genre in which you want to write. If you want to write thrillers for example, then read loads of them and consciously dissect them, analysing what makes them work, and why. Equally, work out what bits don't perhaps hang together, or why a particular character lacks credibility. You have to be a good critic before you can become a good writer. Go to thriller films, and plays too. Immerse yourself in your chosen genre and be alert to what is working well, and selling well, within that. Then, without in any way imitating what others are doing, set out to do it as well as they - or even better.

Now Start Writing

Once you've done a substantial part of your planning, and you have your characters, basic plot and background, then you can start to write. Just start. That's what we all have to do. Simply start writing - however bad you may think it - and keep going for at least two or three hours. You'll be surprised to find that it's soon beginning to flow. I find I write all my new material in the mornings, and then revise and edit it in the afternoons. To write new material for even three hours can be very intensive and terribly draining, so I find that I can't usually write anything new after lunch. So that's when I put on the spit and polish.

Some writers try and write an average number of words a day. I aim for 2000 - about 4 pages of one and a half spaced A4 - but sometimes I might only write 200. But then the next day I might get a sudden burst of creativity and do 4000. But basically it averages out at about 2000 words a day. You might average less, or more. Graham Greene only ever wrote 500 words a day, then he'd stop. Jilly Cooper writes 5000 a day. Above all, go at your own natural pace, but just keep covering the paper and keep at it. As P.G. Wodehouse said, successful writing depends on applying 'the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair'. There's a huge amount of truth in that.

Get Help

If at this stage you don't have an agent or an editor (don't worry, you will!) then ask someone who knows you very well, and whose judgement you trust, to read what you've done so far. Alternatively, sign up for a creative writing course, and get the tutor to read your synopsis or your first few chapters. Not only will this make you feel that you now do have a proper 'reader', you may well find their insights helpful and encouraging. Writing a book is like climbing a mountain, and it's nice to have someone giving you a hand up along the way. But equally, don't show your material to everyone and don't talk about it until you're confident that you're well on the way. Keep it to yourself. And above all, don't give away your plot.

How to Find a Publisher

So you've got your synopsis and you've written the first three chapters, so you're ready for it to be sent out (many novels are sold on that basis). But don't bother sending it direct to the publishers. Publishers used to have 'slush piles' - skyscrapers of unsolicited manuscripts, (approximately 0.1% of which would get published), but no longer. In these more ruthless times publishers will not read any manuscripts that do not come from an agent. So how do you find an agent?

How to Find an Agent

Buy the Artists' and Writers' Yearbook - an industry Bible - in which are listed the names and contact details for all the literary agents. Make a few phone calls first to establish that they do represent novelists (some agents only do non-fiction) and then find out who the relevant person is, and send them your material. This can be quite time-consuming because what you mustn't do is to approach more than one agent at a time. It's insulting, if you're an agent, to know that a synopsis is out with ten other agents. It can also get very murky if more than one of them are interested. So keep life simple. One agent at a time, and if you want the material back, enclose a large s.a.e.. If an agent says that they are not right for you, then get back to them and ask them who they think might be right. A lot of them know each other - by reputation if not personally - and the vast majority would make a helpful recommendation as to whom you might approach next.

Dealing with Rejection

Don't worry if you get fifteen rejection letters. There are lots of very successful authors who only got lucky after months and months of trying. J.K. Rowling famously got loads of rejection slips from publishers (who are all still busy kicking themselves). Other writers are fortunate and find one straight away.

Take Advice

If you have a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend whose girlfriend works for a publishing house or a literary agency, then phone them up, and ask them for advice. People don't mind - in fact they quite often like it because it makes them feel important. And it's only five minutes on the phone and they might well give you a very helpful lead.

What to do when you've got an Agent

Once you have an agent, then it's up to them to find you the right publisher. Don't tell them that you want to be published by Faber for example. Your agent will naturally know which is the right publishing house for you, and they will do their very best to get you there. In return for their efforts, you will pay them between 10 and 15% of what the deal is worth. If they sell foreign rights, then they'll charge 20% as there is usually a sub-agent whom they have to pay.

The relationship between a writer and an agent is vital - it's almost like a professional marriage. You write the best books you can for your agent, who in turn, gets the best deal he or she can for you. You can also bounce ideas off your agent, if they have the time and inclination, as many agents like to be involved in some way, with the creative process. This is because an increasing number of editors are becoming agents - for example Clare Conville, Alexandra Pringle, Peter Strauss - and so they're quite pleased to have a small editorial role.

Once your agent has struck the deal then it's time for a glass of Champagne to celebrate - and then your real work begins. Your new editor will then give you the deadline by which you must complete the book and it's best not to miss it. Publishing a book is like a wedding - the wheels start to turn months in advance. I remember when I was only half way through 'The Making of Minty Malone' seeing a full page ad for The Making of Minty Malone on the front cover of The Bookseller. This was terrifying - and also quite stimulating. My fingers flew across the keyboard that day.

In Conclusion

The fact is that anyone can write a book. And you don't have to have been a journalist first, like I was, and like many novelists were (Helen Fielding, Wendy Holden and Kate Saunders for example). Yes, you have to be able to write well, and to write in your own, distinctive voice, in the genre which suits you best. But you have, above all, to have a good, strong story line which will keep your reader turning the pages. But the fact is that if do you have that, you can - and you will - write a book. But only if you want to do it enough. So good luck and crack on with it and I'm looking forward to reading it soon! yourselves!

Recommended Links

Booktrust.org.uk

Has an excellent section entitled 'Resources for Writers', including the grants and awards which are available.

The Society of Authors

a non-profit membership organisation, founded in 1884 'to protect the rights and further the interests of authors'.

Royal Society of Literature

a membership organisation which organises meetings, readings and literary prizes.

Mslexia

a wonderful quarterly magazine for women writers, it is full of brilliant advice about how to get your work published.

Romantic Novelists' Association

a wonderful organisation, very inexpensive to join, which offers seminars and workshops to both published, and unpublished authors of romantic fiction of all kinds. There is a manuscript appraisal service, and many members have gone on to become bestselling novelists.

Recommended Reads

I read a lot and always evangelise about anything which has made an enduring impression on me and so I'd like to recommend these ten wonderful books to you.

WHAT A CARVE UP!

Jonathan Coe

A riveting satire on the powerful upper classes in eighties Britain as symbolised by the monstrous Winshaw family whose sprawling tentacles reach into every area of public life. Their innocent biographer, Michael Owen, gradually unravels their corrupt grasp on politics, health, newspapers, agriculture and the arts only to discover that they have had a devastating effect on his own life. Though the characterisation is slightly exaggerated in order to entertain, the book is deadly in its accuracy. But Coe is too intelligent, too subtle - and too generous - to make pompous, sweeping judgements about how dreadful the Winshaws are. Instead, he simply shows us them as they are and lets them hang themselves. The spectacle is richly comic, highly entertaining, and often shocking. This is a breathtakingly clever, outrageously funny, and extremely rewarding book which would surely make a marvellous film.

A riveting satire on the powerful upper classes in eighties Britain as symbolised by the monstrous Winshaw family whose sprawling tentacles reach into every area of public life. Their innocent biographer, Michael Owen, gradually unravels their corrupt grasp on politics, health, newspapers, agriculture and the arts only to discover that they have had a devastating effect on his own life. Though the characterisation is slightly exaggerated in order to entertain, the book is deadly in its accuracy. But Coe is too intelligent, too subtle - and too generous - to make pompous, sweeping judgements about how dreadful the Winshaws are. Instead, he simply shows us them as they are and lets them hang themselves. The spectacle is richly comic, highly entertaining, and often shocking. This is a breathtakingly clever, outrageously funny, and extremely rewarding book which would surely make a marvellous film.

THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST

THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST

Anne Tyler

I love Anne Tyler's books and this is my favourite. The hero, Macon Leary, who writes travel guides for Americans who hate travelling, suffers a family tragedy which is threatening to destroy his marriage. He then meets the rather vulgar Muriel, who offers to train his difficult dog, Edward; but Macon finds that Muriel is also retraining him, leaving him decidedly rattled. By turns funny, sensitive, and sad, 'The Accidental Tourist' is a truly life-affirming read. For Muriel's challenge is to teach Macon to live again, but this time to live properly, embracing the chaos and flux - and the fun - of life, rather than remaining stuck in his ossifying old ways.

DISGRACE

J. M. Coetzee

A short, but gripping story about the new political order in South Africa and about the painful compromises made by the whites who choose to stay. David Lurie, an academic, is denounced by his university for having an affair with a student. Willing to admit his guilt, but refusing to give in to political correctness by repenting in public as his dean demands, he resigns and goes to live with his daughter Lucy on her smallholding. Just as he regains his equilibrium he and Lucy are the victims of a savage attack. Though raped, Lucy refuses to denounce her assailants, believing that this is a sacrifice that she must make - as an act of atonement - in the new order of things. Coetzee's prose is spare, but exquisite, and the narrative is engrossing. What is so clever is that although the book is against political correctness, its agenda is a liberal one. This is a profound and very moving novel.

A short, but gripping story about the new political order in South Africa and about the painful compromises made by the whites who choose to stay. David Lurie, an academic, is denounced by his university for having an affair with a student. Willing to admit his guilt, but refusing to give in to political correctness by repenting in public as his dean demands, he resigns and goes to live with his daughter Lucy on her smallholding. Just as he regains his equilibrium he and Lucy are the victims of a savage attack. Though raped, Lucy refuses to denounce her assailants, believing that this is a sacrifice that she must make - as an act of atonement - in the new order of things. Coetzee's prose is spare, but exquisite, and the narrative is engrossing. What is so clever is that although the book is against political correctness, its agenda is a liberal one. This is a profound and very moving novel.

THE HUMAN STAIN

THE HUMAN STAIN

Philip Roth

Another book about political correctness in universities this time in 1990's America, where Coleman Silk, a respected academic has been hiding a secret for fifty years; a secret about his own origins which no-one - not even his wife and four children - knows. A friend, Nathan Zuckerman, sets out, after Coleman's suspicious death in a car crash, to understand how this eminent man managed to fabricate his identity, and discovers how that carefully controlled life came unravelled. A harrowing and completely absorbing novel with a shocking conclusion.

THE SECRET HISTORY

Donna Tartt

You've probably all read this - it's become a modern classic after all - but for anyone who hasn't I urge you to read it and enter the world of preppy Ivy League Hampden college in New England. There, the hero, Richard Papen, who is from an ordinary background in California, falls in with a group of five gilded youths who are studying Greek with him. Enchanted by their glamour, aestheticism and charm, he watches as they descend from affected ennui into total moral decline as they plan the Dionysiac murder of a local farmer. They are all sworn to secrecy, but one of the group cracks, and another murder is soon being planned. Tartt's plot unravels slowly and yet the book is so intense and gripping that the pages seem to turn themselves. Her prose is elegant and erudite, without being self-indulgent, and her descriptive powers are masterly. The book feels a little like Brideshead Revisited in some ways - the poor outsider attracted to, and yet repelled by - his glamourous, socially elevated peers. But at the same time this is a startlingly original, and timeless read. I hope Donna Tartt's long-awaited second novel, 'The Little Friend', won't disappoint after this awesome debut.

You've probably all read this - it's become a modern classic after all - but for anyone who hasn't I urge you to read it and enter the world of preppy Ivy League Hampden college in New England. There, the hero, Richard Papen, who is from an ordinary background in California, falls in with a group of five gilded youths who are studying Greek with him. Enchanted by their glamour, aestheticism and charm, he watches as they descend from affected ennui into total moral decline as they plan the Dionysiac murder of a local farmer. They are all sworn to secrecy, but one of the group cracks, and another murder is soon being planned. Tartt's plot unravels slowly and yet the book is so intense and gripping that the pages seem to turn themselves. Her prose is elegant and erudite, without being self-indulgent, and her descriptive powers are masterly. The book feels a little like Brideshead Revisited in some ways - the poor outsider attracted to, and yet repelled by - his glamourous, socially elevated peers. But at the same time this is a startlingly original, and timeless read. I hope Donna Tartt's long-awaited second novel, 'The Little Friend', won't disappoint after this awesome debut.

DIRTY TRICKS

DIRTY TRICKS

Michael Dibdin

A savagely funny thriller set in contemporary Oxford and with an anti-hero who is unlovable, unreliable - in fact thoroughly bad - and yet such brilliant company that you find yourself rooting for him as he sets out to destroy the dull but happy suburban marriage of Denis and Karen, and soon finds that a bit of adultery has somehow led to murder. The first person narration takes us right inside the head of this erudite, Machiavellian, indeed almost diabolical, character. We may not like him, but he is fabulously entertaining and the humour is as black and glittering as anthracite.

FOUR BARE LEGS IN A BED

Helen Simpson

Helen Simpson's first collection of short stories established her as one of Britain's finest writers, and won her the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year award as well as a place on the coveted Granta Best of Young British Novelists list in 1990. Loads of you will have read the wonderful 'Hey, Yeah, Right, Get a Life' collection published last year, but I think this is even better. It's concerned with her usual themes of love, marriage, independence, sex and motherhood and there's one wonderful story, written in the style of a Greek play, with a chorus of two midwives. Helen Simpson's prose is elegant and acutely observed; she has a shrewd, darting eye - a bit like Muriel Spark - and no telling detail evades her mischievous gaze. All Simpson's short stories are excellent - she has made a slightly unfashionable form her own - but, like many of her fans, I wish she'd write a novel as well.

Helen Simpson's first collection of short stories established her as one of Britain's finest writers, and won her the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year award as well as a place on the coveted Granta Best of Young British Novelists list in 1990. Loads of you will have read the wonderful 'Hey, Yeah, Right, Get a Life' collection published last year, but I think this is even better. It's concerned with her usual themes of love, marriage, independence, sex and motherhood and there's one wonderful story, written in the style of a Greek play, with a chorus of two midwives. Helen Simpson's prose is elegant and acutely observed; she has a shrewd, darting eye - a bit like Muriel Spark - and no telling detail evades her mischievous gaze. All Simpson's short stories are excellent - she has made a slightly unfashionable form her own - but, like many of her fans, I wish she'd write a novel as well.

SAVING AGNES

SAVING AGNES

Rachel Cusk

Helen Simpson is peerless when it comes to writing about motherhood in fiction - and in 2001 Rachel Cusk in 'A Life's Work', was equally acclaimed for her non-fiction treatment of this theme. I love Rachel Cusk's novels too, which are quietly gripping, told with irony and insight, and written in fine, resonant prose. This debut novel, which won her a Whitbread prize, is a lovely introduction to her work if you haven't yet had the pleasure.

FROST IN MAY

Antonia White

Fernanda Grey, Protestant daughter of a Catholic convert is sent to a convent in 1908 where she soon learns to conform to the rigid authoritarianism and petty cruelty of the nuns whose mission is to 'break' each pupil like a horse - to tame her for Christ. The book remorselessly charts the series of small emotional humiliations they inflict on the heroine, which have entirely the opposite effect to the one they planned. This is a brilliant evocation of convent life - you can almost smell the incense - and the characterisation of the nuns is excellent. I re-read this classic novel every two to three years. If you haven't read it - don't miss out.

Fernanda Grey, Protestant daughter of a Catholic convert is sent to a convent in 1908 where she soon learns to conform to the rigid authoritarianism and petty cruelty of the nuns whose mission is to 'break' each pupil like a horse - to tame her for Christ. The book remorselessly charts the series of small emotional humiliations they inflict on the heroine, which have entirely the opposite effect to the one they planned. This is a brilliant evocation of convent life - you can almost smell the incense - and the characterisation of the nuns is excellent. I re-read this classic novel every two to three years. If you haven't read it - don't miss out.

THE EYRE AFFAIR

THE EYRE AFFAIR

Jasper Fforde

This is one of the most inventive books I've ever read - a brilliantly clever mix of some existing genres, and yet it's startlingly original too. To get a flavour of it imagine a collision between 'Alice in Wonderland', 'A Brief History of Time', 'The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy', 'Farewell My Lovely', 'Being John Malkovich', and 'Jane Eyre'. It's a wildly whacky and very funny mix. The heroine, Thursday Next, is a literary detective hot on the heels of the evil Acheron Hades who enters the manuscripts of classic books and kidnaps minor characters and holds them to ransom. The cast also includes a pet dodo, some bookworms who eat propositions and semi-colons and then do raNdoM caPiTaliSaTioN, and there are cameo appearances by William Wordsworth and Mr. Rochester. Who would have thought a book set in Swindon could be this entertaining?

And finally...

There is so much wonderful commercial fiction on the market at the moment - the last five years have seen a flowering of hugely entertaining and clever books by Marian Keyes, Wendy Holden, Jessica Adams, Lisa Jewell, Polly Samson, Anna Maxted, Jenny Colgan, Cathy Kelly et al. (no room to mention them all). For a taste of their talents which will surely lead you to their books, I thoroughly recommend the four short story collections published by HarperCollins in aid of Warchild, and No Strings International: 'Girl's Night In', 'Girls Night Out: Boy's Night In', 'Big Night Out' and, most recently, 'Ladies Night'. Four wonderful books in support of a very worthwhile cause. Enjoy.

RIP Woolies

Daily Mail

11th December 2008

Where do you think David Cameron bought his Christmas wrapping paper this year?

His wife's Bond Street stationers, perhaps? Or some achingly fashionable designer boutique? Not exactly.

Last weekend, the Tory leader was pictured emerging from the Notting Hill branch of Woolworths, clutching a huge bag filled with wrapping paper and toys that he'd picked up in the store's closing down sale. I didn't know whether to cheer or despair.

On the one hand, I am delighted that Cameron is a fan of Woolies. On the other, it's so desperately sad that - barring some last-minute miracle - the chain is to disappear from our High Streets.

By a curious quirk of fate, last month I was in the same branch that Cameron visited when I overheard the manager say that trading in the firm's shares had been suspended. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that I felt like crying at the loss of a lifelong friend.

Looking back, the signs had been there for months - the endless '3 for 2' banners everywhere that had begun to feel not so much a tempting offer as a sign of desperation; the low prices that seemed to have become fatally low.

Most alarming was the closure, six months ago, of a huge branch I occasionally visited in North London. And now the axe has fallen on them all.

In probing what's gone wrong, most armchair analysts have blamed the diversity of Woolworths' merchandise for its demise. TV reporters were filmed emerging from a branch looking perplexed, holding up a CD, toy car, girls' cardigan, tin of paint and bag of pick 'n' mix sweets - like the sad relics of some long-ago era.

This puzzling variety, they seemed to be saying, was somehow a failure of the shop. On the contrary, as any Woolworths-worshipper like myself will tell you, this is what gave Woolies its unique appeal.

A true Aladdin's cave

Woolworths is and has always been the ultimate pick 'n' mix store - and not just at the confectionery counter. It was a true Aladdin's cave in which you could find anything and everything - usually on one floor and always at low prices.

Where else could you pick up a garlic press, DVD player, lightbulbs, ream of A4, popcorn maker and Cinderella dressing up outfit, all within 20ft of each other and for less than £50?

But the real Wonder of Woolies - for me, at any rate - was that it remained a paradise for children. Everything that children love was there - toys, sweets, DVDs, computer games, art materials, trendy clothes and books.

In a decade where so many toy shops have been driven under by the retail behemoths Toys R Us, Tesco and Amazon, Woolies was the only place where children could run up and down the aisles, like mine do every Saturday, comparing Barbie dolls with Bratz, Hot Wheels with Road Rippers, and V-Tech laptops with Fisher Price, without fear of reprimand from a jobsworth store manager.

My five-year-old, Alice, adored going to Woolies to spend her pocket money, just as I did four decades ago.

As we walked down my local High Street, even my two-year-old would start straining at his buggy straps. By the time he'd spotted the iconic red 'W', he'd practically burst out of his restraints, like some miniature Incredible Hulk.

It wasn't hard to work out why they liked it so. In Woolworths, my daughter knew that, even at the age of five, she had spending power. She could buy a budget fashion doll or pony for a pound each.

Good behaviour over the week might be rewarded with something I would buy for her, perhaps from the excellent range of Ladybird children's clothes. And, of course, she was always allowed a little something from those bins of multi-coloured pick 'n' mix.

Memory lane